If you could kindly tap the ❤️ at the top or bottom of this newsletter it will make it easier for other people to find this publication. Ahéhee'! བཀའ་དྲིན་ཆེ།! 謝謝! Thank you! ขอบคุณ!شكرا ! תודה! Спасибо! धन्यवाद! Cảm ơn bạn! អរគុណ! Merci y Muchisimas gracias!

I first came to Pun Pun 15 years ago. I was then leading American university students throughout Asia, hoping to engage them with other ways of living, other ways of seeing and dreaming that were far different than what they had grown up with. As it turned out, those years traveling with young adults in “off-the-beaten-path” locations seemed to change me just as much, if not more so, than them. My initial intent was to expose my students to various approaches to the teachings of the historical Buddha. I was (still am) convinced Buddhism was able to offer modern society a sort of global ethic, a shared view that might better prepare my students for the troubled world they would soon be inheriting.

Yet what I soon discovered wherever we went, whether high in the mountains of the Himalaya or anywhere in Southeast Asia, was that it was seed that was the dominant thread weaving all life together, not religion. Seed consistently offered a tangible method, a living mythology of shared commitments to a time beyond now, far more so than any religious view I had encountered. It was not a god or any guru, but food that ultimately brought people together, forged meaningful alliances and nourished all purpose and faith. As such, I eventually shifted my primary focus from religion to food, seeking out not Tibetan Lamas but master keepers of Seed. First in India, then Nepal, Tibet, Sikkim and finally, Northern Thailand, where I met my beloved wife, at a small seed farm that soon became my home, called Pun Pun.

Pun Pun is, first and foremost, a seed bank. The name itself implies as much. Pun Pun, is a Thai term meaning “a thousand varieties”. Our communities’ founder, Jon Jondai, originally purchased the land, which was undesirable at the time he bought it, with hopes of building adobe homes here, which he did in fact do and continues to do. He was the first person in Thailand to do this and now thousands of people have learned how to build simple mud homes at Pun Puns Center for Self-Reliance. Yet, as anyone who has worked within the realm of “sustainable living” can intimately attest to, whether one’s initial interest in such pursuits sparks from say, appropriate technology, water treatment, natural medicine, or any other related angle, all roads eventually lead back to food and Seed. For without these, little else is possible.

More an “un-intentional community” than anything resembling a place built by design, over the years Pun Pun has attracted thousands of people from all over the world hoping to reconnect with the ancestral knowledges that modernity has managed to shield most from. In addition to learning how to make simple homes out of natural materials, confidently gather medicines from wild herbs, etc. community members and guests spend most days gardening, harvesting and preparing meals for anywhere from 20–100 (or more) people. Everything revolves around food here. Even the way Thai’s say hello;“Gin kao liang mai?”, which translates loosely as, “Have you eaten yet?”

My beautiful wife presenting many herbs gathered from our garden for lunch.

…

There is no official mission statement at Pun Pun. There is no leader and no rules to guide. The only paths are the ones that naturally arise through relationships forged while experimenting with the land. None of the founders of Pun Pun were expert farmers, builders or cooks when they first arrived here, and no experts came to teach them. Arguably, there still are no experts here today, only simple, hard working, mistake-making humans dedicated to coming together every day, even when feeling overwhelmed, uninspired, vulnerable and under-slept, with fellow community members, total strangers, lots of noise, lots of silence and always the land, in an ongoing effort to eat well, and live well.

Days here are directed by the needs of soil, by the poetry of rain, the intensity of the Sun and the sporadic cries of our growing children. At first, visitors are usually a bit confused and disoriented. Being well conditioned to modernities consistent timeframes and formal, systematic communication styles, they expect a more rigid schedule to follow, someone to spell out for them exactly what to do. We offer little, if any of this. We merely provide the conditions for sprouting. It can be awkward. Yet after a week or so, the indigenous soul in them, that little spark of ancient human-ness that knows how to self motivate, make an effort and listen well, starts to wiggle a bit, slowly coming back to life. Listening again to the sounds of birds, taking cues from the waxing moon, lost memories emerge, and a more natural rhythm is again found.

Rare are the days that we even have a set plan for what meals we are going to eat. Usually, such inspirations are sparked when two new friends collide serendipitously in the gardens, while weeding, harvesting or planting seed. They say hello, in each other’s respective mother tongue and strike up a conversation together. Recently it was the coming together of a woman from Palestine and a young man from Israel that eventually initiated a particularly delightful feast. Though I cannot say for certain, I imagine there was a moment when the sudden realization of who “the other” was ignited strong emotion. Our socially constructed perceptions of who we think we are have rather curious side effects indeed. Yet as they sat side by side, hands in the soil, the heat of the new day challenging them to react in new ways, they spoke not of their governments’ curious narratives but instead spoke of food.

That evening they made a meal together for the entire community. At Pun Pun we only have one kitchen and one giant table. Every meal is eaten together, and all food is prepared collectively. “What foods grow together, go together.”, we often say. We find inspiration from whatever the season brings us, we listen deeply and encourage creativity. The same holds true for the people who visit us. We seldom know who will be coming to volunteer with us, nor from where they will be arriving from. We accept everyone and find beauty in every language, every seed. Every unique view is welcome at our dinner table and there is always enough room.

Many of the people who volunteer with us come from places where war is the norm. To even eat the cuisine they love is seen to many they regularly engage with as a threat. Yet here, over food, in a colorful explosion of diverse cultural cross-pollination, it is usually peace that breaks out, not war. We learn from each other as we prepare the many foods that carry with them myriad place-based stories. These stories rise slowly at first until bellies are full. Then they flow as freely as the homemade wine we share and begin to merge with other stories, stories untold for lifetimes yet suddenly remembered in full, not only subtly whispered but exuberantly sung over the joyful rhythms of falling tears and belly shaking laughter. And yes, sometimes tears fall. Holy Grief, offering beauty, the most necessary ingredient of all.

We dined on Za’tar and Maqlubeh that night. Hummus, shakshuka and of course, sticky rice, mangos and naam prick! The table was filled with new friends from around the world. A couple who had escaped from Myanmar’s ongoing, overlooked civil war had arrived to our farm a week earlier. They prepared Burmese tea salad for us. There was a man from Tibet and several students from mainland China. There were two Americans, a woman from Canada and at least twenty or so Thai. A young woman from India made chapati. It went so well with the hummus! It was her first time traveling abroad. She was mesmerized and feeling sleepy. A young family from a nearby “hill tribe” village joined us too. They shared wild mushrooms and fermented plums. There was a gentleman from Russia and the children all played with him. Few of us could really understand much of what anyone else was saying, each of our languages, so different, so unique. But as our bellies began to overflow, our need to be understood gave way to the need to love and be loved. Soon, the pleasant sounds of munching inspired some to dance.

First, the man from Israel stood up, raising a glass of wine. He made a prayer for peace and shared a Shabbat song. The woman from Palestine then stood too, to join him. She was familiar with the song and chimed in. Not long into the second verse we all rose and did our best to sing along, our arms wrapped around each other like dolmas. The kids ran circles around us all, as one dance turned into two, two into three, four, and on into the night as we shifted from the dining hall to the campfire glowing under a shimmering sea of stars overhead.

At one point, amidst our broken-languaged efforts to share stories, a handful of us realized we carried shared admiration for an elder seed saver from New Mexico named Martin Prechtel. Years ago a volunteer from The States had left several of his books in our library and one of our new friends was reading aloud from one of them a particular verse that seemed to encapsulate the day;

“Turn that worthless lawn into a beautiful garden of food whose seeds are stories sown, whose foods are living origins. Grow a garden on the flat roof of your apartment building, raise bees on the roof of your garage, grow onions in the iris bed, plant fruit and nut trees that bear, don't plant 'ornamentals', and for God's sake don't complain about the ripe fruit staining your carpet and your driveway; rip out the carpet, trade food to someone who raises sheep for wool, learn to weave carpets that can be washed, tear out your driveway, plant the nine kinds of sacred berries of your ancestors, raise chickens and feed them from your garden, use your fruit in the grandest of ways, grow grapevines, make dolmas, wine, invite your fascist neighbors over to feast, get to know their ancestral grief that made them prefer a narrow mind, start gardening together, turn both your griefs into food; instead of converting them, convert their garage into a wine, root, honey, and cheese cellar--who knows, peace might break out, but if not you still have all that beautiful food to feed the rest and the sense of humor the Holy gave you to know you're not worthless because you can feed both the people and the Holy with your two little able fists.”

As the moon shined down over us, and rice deserts were presented graciously by the Thai community, we continued sharing poems and passages inspired by the sweetness in our bellies and hearts as we stared upwards into the nighttime sky. For how long had this moment been missed, distracted as we too often are by fast food and fast culture?

…

As the days went on, the raw messiness of being human rose again like weeds. Little arguments surfaced between us as we slowly got to know each other more. The initial intoxicating love affair with each other we felt the night of the feast soon matured into everyday reality. But having only one table, only one kitchen and only one rice field requires of us all an ancient skill, that of continued coming together, regardless of whether we feel like it or not. We continue feeding each other, we continue learning how to see the world from someone else’s eyes and from someone else’s belly. Sometimes, after an argument, the tension between two is so great that one (or both) refuses to venture down to the kitchen, skipping a meal altogether. But eventually the heart requests companionship, the belly demands to be filled and the community expects us to lend a helping hand. Life then naturally pulls us back into Right Relation, like a healthy, untamed, pulsing river.

We all must work together. The children must be fed. The corn won’t grow without our shared care. And as we tend to what matters most, we laugh, we cry, we gossip and sing, we get hungry and eventually forget altogether as to why it was that we ever were mad in the first place. Food has an eternal, borderless, deeply magical way of reminding us of that which matters most.

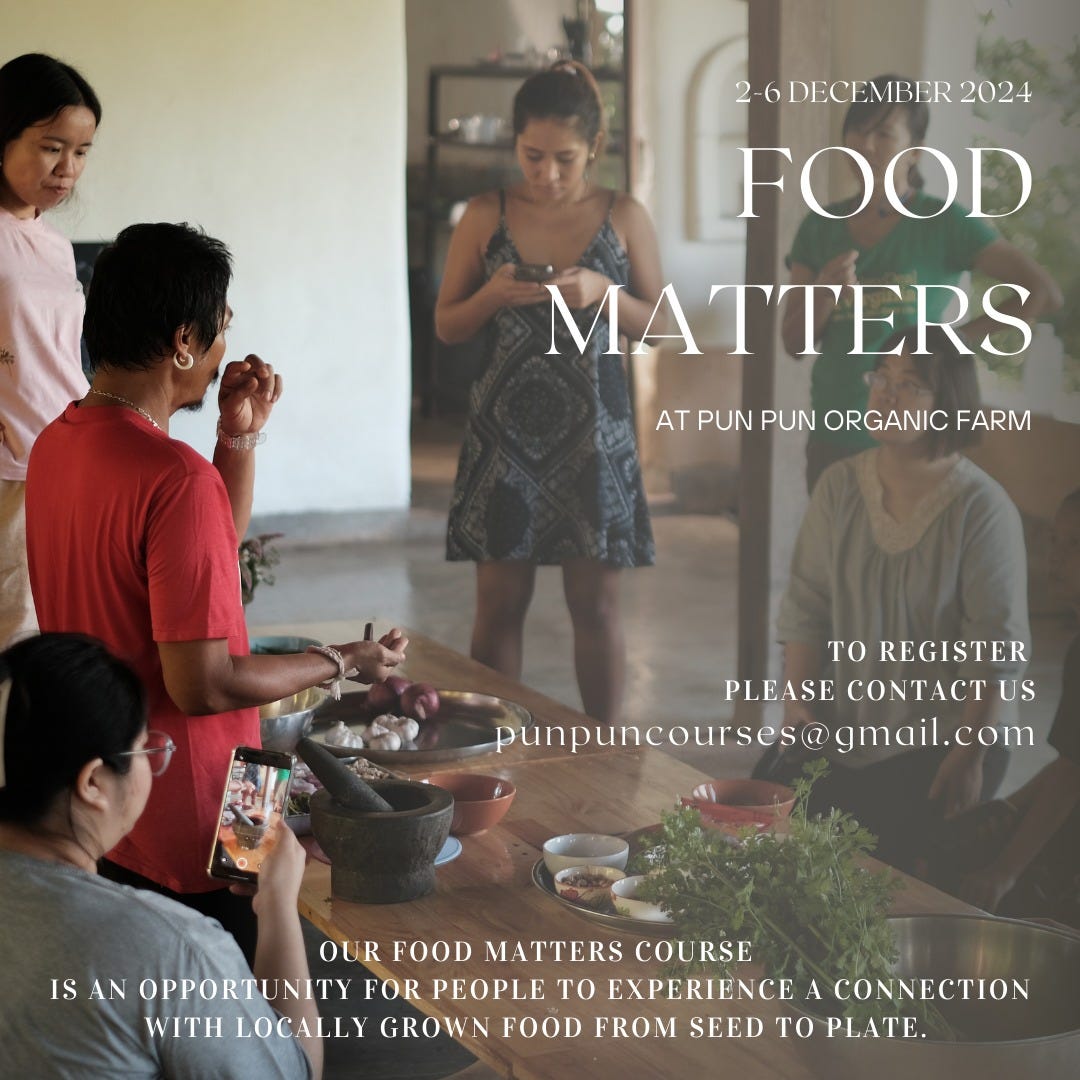

Special Opportunity Alert!

We will be hosting a course at our farm in December the delves deeply into what was shared here. There are still a few spaces available.

All are welcome!

For more information, please write to us directly at: punpuncourses@gmail.com

If you could kindly tap the ❤️ at the top or bottom of this newsletter it will make it easier for other people to find this publication. Ahéhee'! བཀའ་དྲིན་ཆེ།! 謝謝! Thank you! ขอบคุณ!شكرا ! תודה! Спасибо! धन्यवाद! Cảm ơn bạn! អរគុណ! Merci y Muchisimas gracias!

#mayallbeingsbehappyandfree

Share this post